Tracing the history of Middle Eastern racial classification in America

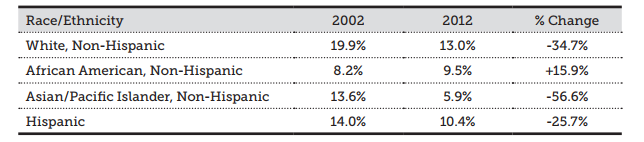

A few weeks ago, I was working on a grant that would help to decrease tobacco-related health disparities among minority populations. The table I was using looked a little something like this:

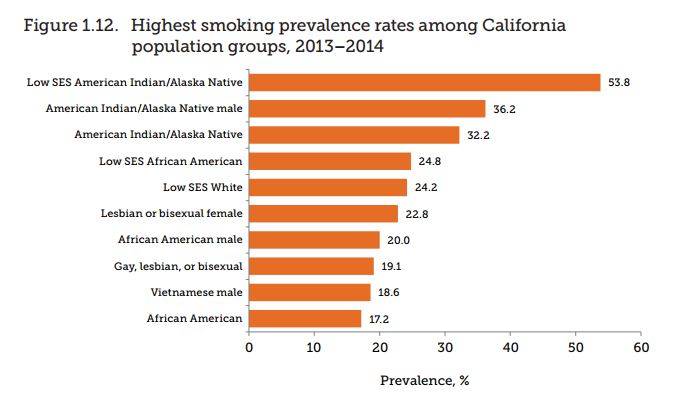

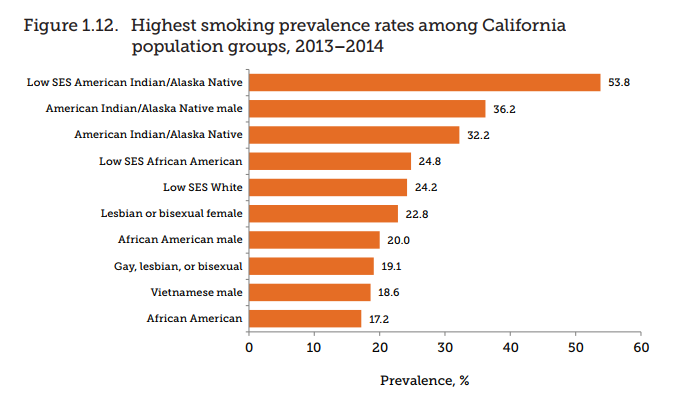

And this was the graph:

In fact, throughout most of my undergraduate and post-graduate career, I became very familiar with the “Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, African American/Black, Asian/Pacific Islander” dynamic. It was clear that my professors thought this summed up every major demographic in America nicely, but to me, I never understood why Middle Easterners and North Africans such as ourselves weren’t represented in these statistics.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the official agency tasked with counting every person in the country, the definition of being white in America is “a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.”

Middle Easterners and North Africans (also known as MENA) are therefore an invisible group here in America. Yes, we are somewhat represented through the American Community Survey, but since it’s not an actual count, disputes about the exact number of MENA people living in America ranges from 1.8 million to 3.7 million people.

If it seems a little counter-intuitive to be considered white, that’s because it is. During the first wave of immigration in the 19th century, Arab Christians trying to escape persecution in the Middle East, while also trying to avoid the racist restrictions of Asian immigration, won key court cases to change their racial classification from “Mongolian” to “Caucasian.”

In 1909, Levantine Christians pooled their resources in Los Angeles County to win the first case to classify Middle Easterners as Caucasian. In his statement, the lead defendant George Shishim argued: “If I am Mongolian, then so was Jesus, because we came from the same land.”

The reigning ideology of that time was based on the erroneous philosophy of “Social Darwinism,” which ranked different races along a hierarchy with white people at the top. According to their logic, Jesus MUST be white, because he is the son of God and the ultimate human. And if Jesus is white, then Middle Easterners must be white as well. Essentially, Shishim leveraged Jesus’s ethnicity, who was indeed a Middle Eastern man, as a way to assert his own whiteness and gain citizenship into the United States.

Today however, times have changed, and most people understand that every ethnicity is equal and no one group of people is inherently superior. On the other hand, the concept of race is an institutionalized social construct with very real consequences. Because of this, accurate statistics need to be taken in order to understand, identify, and address the needs of each demographic.

For example, let’s go back to the second graph in this article:

By looking at this graph, it is clear that the people who suffer most from tobacco addiction are Native Americans with a low socioeconomic status, followed by all Native Americans. Because of this evidence, the California Public Health Department can design and implement cessation programs that specifically target areas with large numbers of Native Americans.

Meanwhile, we have no idea what the smoking rate is for Middle Easterners and North Africans. I would imagine that it’s pretty high, given the wide cultural acceptance of hookah and other smoking products. However, in this graph, we are lumped in with the rest of the white population, simultaneously skewing results for white demographics without our presence being recognized.

Since the last time the U.S. Census was taken in 2010, there has been a discussion on whether or not to add a MENA category into the Census when it comes out in 2020.

There is some pushback on both sides, however. While some believe that including a MENA category is an important step to recognizing our identity here in America and addressing our needs, others are wary that registering as MENA will make it that much easier to be targeted, which happened after 9/11.

However, one thing is certain: as long as MENA as a racial category within the U.S. Census Bureau does not exist, we do not have the basis of evidence needed in order to help the people within our own community.

Marianne M. Boules is a project director and policy analyst living in Riverside, California, where she received both her Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Public Policy. Marianne enjoys rock climbing, writing, and hanging out with her husband Tony.

If you would like to contribute to the Coptic Voice, please send an email with your bio and topic of interest to CopticvoiceUS@gmail.com